Malaysian by nationality, Chinese by ethnicity and heritage, Brit by circumstance; by way of Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and London. 🇲🇾 + 🇸🇬 + 🇦🇺 + 🇬🇧 = ? In which I spill the (oolong) tea about my identity, my heritage, and the distinctions of different Chinese groups (from the Mainland to Overseas) against a pastel-pretty historical street that formed part of the backdrop of my childhood in Singapore.

🇸🇬🇸🇬🇸🇬

THE QUESTION: IDENTITY

In the advent of social media being a breeding ground for woke-ness, the marginalised can make their voices and grievances heard. This democratisation of opinion has created a platform where anyone with access to the internet can make their thoughts heard and hold conversations in a safe space. One obvious upside is that injustices are harder to sweep under the rug, especially when topics rise on a wave of hashtags and call wider attention to issues that a majority remain blissfully unaware of. Information is power, and when used properly social media is a wonderful tool to inform and empower.

There’s a downside, naturally. Identity has become politicised, weaponised, even. For every well-meaning person raising a valid point and willing to engage in conversation, there may be one who use their identity to avoid discussion of differing opinions, instead throwing around unfounded accusations of (among others) racism, discrimination, colonialism, cultural appropriation, and oppreshuuuuuun! This is incredibly damaging because by using identity to shield themselves from discourse, they are in a way reinforcing their “otherness”, which is contradictory to the point that all deserve equality regardless of heritage and identity.

THE ANSWER: MY IDENTITY

But once and for all, I am an Anglo-Chinese-Malaysian chimera. My nationality is Malaysian. I hold a Malaysian passport and I have Settled status in the U.K where I primarily reside. I speak English with a trans-Atlantic accent (a strange blend of Received Pronunciation with occasional North American twangs as well as a Malaysian accent that fluctuates depending on who I am speaking with), fluent Malay, and not-at-all-fluent Mandarin (Cantonese, even less so). I introduce myself as Malaysian-Chinese for the sake of simplicity but ultimately, I consider myself a product of my upbringing: I am a global citizen.

THE QUESTION: HERITAGE

With the complicated question of my identity answered (which, I must stress, is a fluid and ever-changing concept), that leaves the easier but no less complex question: my heritage. A question every mixed-raced person or person of an ethnic minority living in a predominantly white society gets is “Where are you from? No, where are you really from?” Because it doesn’t matter if you grew up in, say, Berkshire, or have a Saaf Landaaan accent – if you look different, you are (to some, at least) different. And their curiousity won’t be satisfied until you give them the answer they want (How far back to you want me to go? The Qing dynasty? Baby, sit down and let me tell you about the times I went back to the motherland) to enforce their perception of your otherness.

“Where are you from?” is a question that is loaded, even when asked not from a place of malice. Especially when the person being asked has been subject to racism and discrimination. I have mixed-raced British friends who say they were considered “not white enough” when in Europe and “not Asian enough” when in Asia. I myself am no stranger to discrimination, whether in Malaysia for being part of a large Chinese minority (negative stereotypes include being shrewd, greedy, and money-minded) or in England and other predominantly-white countries (”You Chinese? You eat dogs?” The answer is sort of – I eat hot dogs and corn dogs. Yummy).

THE ANSWER: MY HERITAGE

Racism, I cannot abide. Ignorance, I can tolerate, because even the wise were once fools. Those who know not but know they know not and want to know more are to be lauded, and the only way to know more is to ask questions. Which is why, when I receive the question “Where are you really from?” I try not to be affronted but instead do my best to explain. After all, if I shut someone down for their innocent curiousity the experience may make them afraid to ask questions in the future, narrowing their horizons. So, if I have the time, I take the opportunity to tell them what I know about the Chinese disapora and the Chinese Civil War (not neccessarily in that order).

My ethnicity is Chinese. I am 4th generation Chinese. My maternal great-grandfather was born in Imperial China. His party formed the Republic of China then set up government-in-exile in what is now modern-day Taiwan. You can read more about my family history in relation to Taiwan, here. My grandfather was born in Singapore, his daughter (my mother) and I were born in Malaysia. As with many of the Chinese in Malaysia, I practise some Chinese traditions while I roll my eyes at others. I value my Chinese heritage and I closely follow Chinese interests. My heritage forms a part of my identity, from wearing red on Chinese New Year to taking the Chinese horoscope more seriously than the Western zodiac.

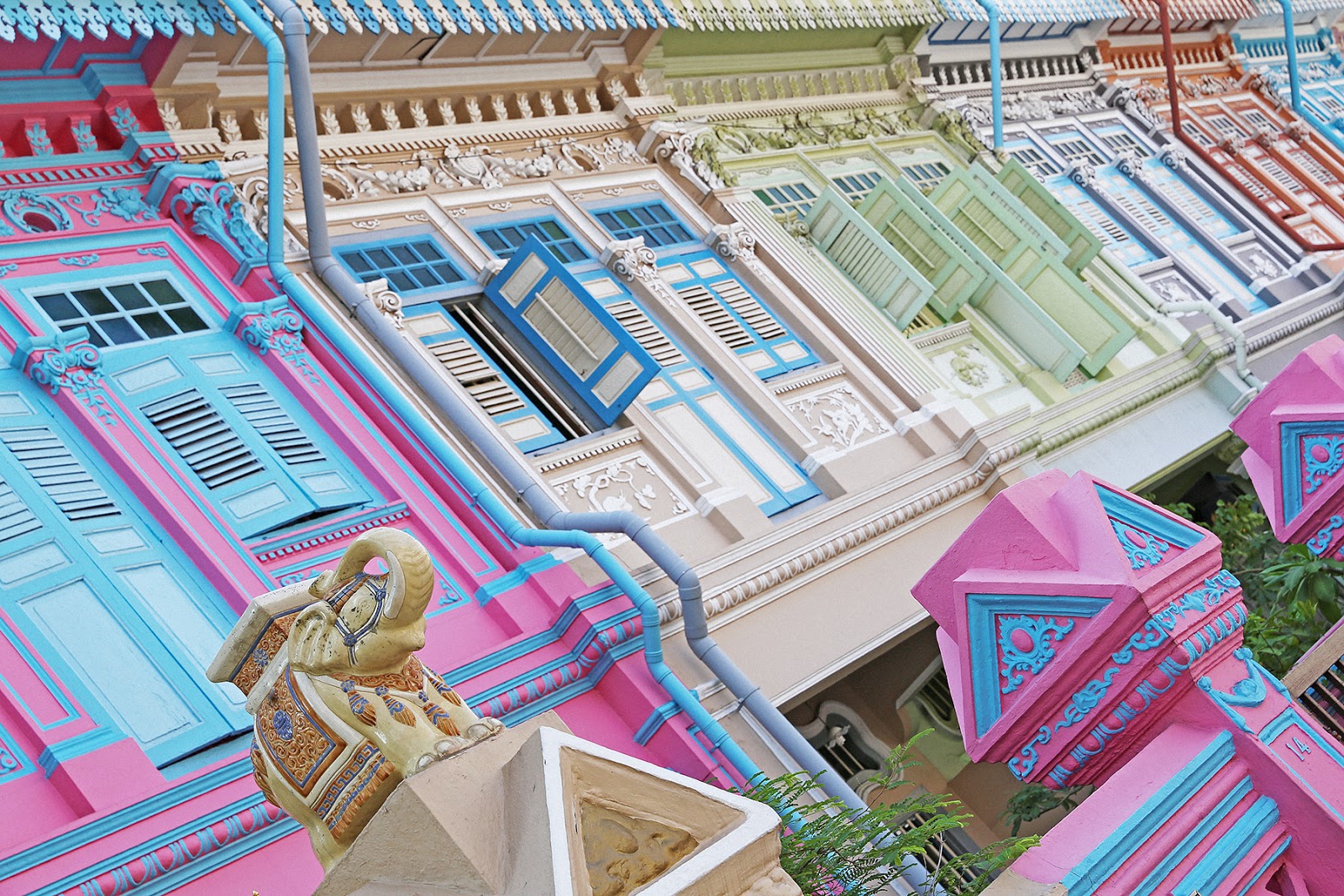

The Peranakan houses of Joo Chiat Road. Yours for a cool S$5,000,000 and up. Personally I prefer my late grandfather’s house in Bukit Timah, at least his street wasn’t thronged with people taking photos (guilty as charged).

“If you’re Chinese, what are you doing outside of China?” Same as you, really – just living my life.

“What kind of Asian are you?” Try “what kind of Chinese am I”.

華人(HUA REN), 中國人 (ZHONG GUO REN), 華侨(HUA QIAO), & 華裔 (HUA YI): 4 DIFFERENT DISTINCTIONS OF CHINESE PEOPLE, AND WHAT DEFINES THEM.

華人 (HUA REN) – ETHNICALLY CHINESE

All people of Chinese descent are 華人 (Hua Ren), regardless of their nationality and whether or not they practise traditional Chinese customs. Grammatically, 華人 (Hua Ren) means someone of Chinese ethnicity, although it’s generally used to refer to people outside the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

中國人 (ZHONG GUO REN) – CITIZEN OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

In oral usage in the People’s Republic of China (PRC, also known as Mainland China), 中國人 (Zhong Guo Ren) means someone ethnic Chinese-looking by racial appearance. In oral usage among the Chinese diaspora and outside Mainland China, 中國人 (Zhong Guo Ren) refers to the population of the People’s Republic of China, specifically those subjected to the Cultural Revolution. 中國人 (Zhong Guo Ren) are also known as Mainlanders and PRCs. The terms Mainlander and PRC are sometimes used with a derisive and snobbish tone by Chinese outside of Mainland China (Taiwanese, Hong Kongers, and Overseas Chinese) to distinguish themselves as more progressive, modern, and refined.

華侨 (HUA QIAO) – OVERSEAS CHINESE (FIRST GENERATION)

The PRC definition of 華侨 (Hua Qiao) is a Chinese citizen, or someone who could claim citizenship, but who is resident abroad. In actual everyday usage, 華侨 (Hua Qiao) refers to ethnic Chinese with overseas nationality but is usually restricted to first-generation immigrants.

華裔 (HUA YI) – OVERSEAS CHINESE (2ND GENERATION OR MORE)

華裔 (Hua Yi) is similar to 華人 (Hua Ren) but signifies a slightly more distant connection. The word itself implies ‘of Chinese extraction’. 華裔 (Hua Yi) can be used to refer to Overseas Chinese such as myself. I am part of the Chinese population of Malaysia who are ethnically Chinese and practise Chinese customs (some identify as Chinese more so than others) but my nationality (and to some extend, wider identity) is Malaysian.

So, to summarise: All ethnically Chinese people are 華人(Hua Ren). All citizens of the People’s Republic of China are 中國人 (Zhong Guo Ren). All first generation Chinese people outside of PRC are 華侨(Hua Qiao). All 2nd (or more) generation Chinese people outside of PRC are 華裔 (Hua Yi).

Identity, heritage, and all its subtle nuances can be a complex thread to unravel. Especially if you grew up and lived around the world. In my next story, I’ll show you my childhood haunts in Singapore as well as some of Singapore’s newer delights.