Graz’s makers don’t make it easy to profile them. This is a city where the produce, not the producers, is the protagonist. It’s arguably easier to open a prized bottle of local Muskateller wine or celebrated pumpkin oil than prise self-serving conversation from the city’s citizens. Here, everyone would much rather tell you about their terrain and traditions than their individual tales.

It’s fitting for a corner of the world where community thrives and quality speaks louder than any soundbite could. Graz might be Austria’s second city, but ask anyone here what they love about their city, and they’ll soon tell you its size.

Unfettered by this modest maker mindset, on my recent third visit to Graz I set out to meet a handful of the makers that make (and keep) Graz such an exemplary example of a city clinging on to its ways of life rather than roaring towards overtourism. I wanted to learn more about those who make Austria’s second city tick, from the winemakers growing vines on its slopes to the teams providing guests with welcoming beds for over a century. Here’s where to go and who to meet to see Graz through the eyes of its citizens.

A Family-Owned Stay: Meet Philip Florian at Parkhotel

Any good city break starts with a home away from home. In Graz, that can often mean a family’s home, but in the form of a hotel. Across the city, numerous family-run hotels continue to flourish, often with their owners living on-site. Forget soulless chain hotels; in Graz, ancestral home comforts still thrive.

“Family-owned businesses need to remain. It’s very important for every city. For every place,” Philip Florian, the fifth-generation General Manager of Parkhotel, tells me over coffee shortly after checking in. “Take my family; we aren’t only investors here. This is our place, our home, and we’re citizens here. We’re part of the city, and the city is part of us.”

It’s a timely conversation as overtourism tears through many of Europe’s cities, stripping them of much of their soul. Behind us, two monochrome photos of his great-grandparents – August and Maria – hang on the wall. Since childhood, the hotel has been a key part of Philip’s life. It wasn’t just his parents’ workplace; their home was adjacent. A home where he would run through corridors and dash into the kitchen – a kitchen that now operates one of Graz’s most acclaimed restaurants.

“I remember her being outside next to the garden that she always arranged, I remember it like it was yesterday”, he reflects on his grandma and the rose garden she planted, now the al fresco dining area’s centerpiece. “She was always arranging the flowers for the tables every day.”

Yet Parkhotel’s history predates Philip’s family. It’s been a guest house for 450 years. Since renamed for the bounty of parks nearby – 60% of the Graz is green spaces – the hotel has been renovated, adding an indulgent spa and growing to 68 rooms without losing any of its old-world Austrian charm.

Be it morning, day or night, you’ll find Philip somewhere around the hotel. Especially at lunch when he prefers to be in the dining room welcoming guests and offering them insider tips, such as where to see horses in the countryside or which courtyards deserve seeking out in the Old Town. But when he’s not at the hotel, he’s with his two kids – no morning at work begins before he has dropped them at school.

“There’s no AI that can replace the smile of our employees,” he continues, as our conversation turns into a second coffee and detours into the main challenges facing the hospitality industry. Soon, we have discussed everything from sustainability in Graz (“Sustainability is also a social way, ensuring employees stay and feel welcome in the team.”) to how one of the hotel’s chefs just earned an award from the government due to his four decades of service.

How do you explain Graz in one sentence? I asked before heading out sightseeing. “It’s hard. Because very often, you’re trying to explain a feeling. It’s the feeling of being here and being welcome.”

Caffeine with Conversation: Meet Eva Berghofer at Coffee Ride

It’s a little after 9:22 when I arrive at the pocket-sized Coffee Ride cafe, passing a ‘Sex sells but I sell coffee’ sign and a handful of coffee-sipping cyclists on the cobbled terrace out front. Not that there’s any point arriving before that precise time; Eva Berghofer doesn’t open her door before 9:22, locking them at 17:07 on the dot.

“There is no real reason. Well, there is a small reason behind it, but it’s just because some customers open their shops at 10. So if I open at 9.30, it’s, yeah, maybe stressful. So 9.22 is eight more minutes,” she announces between laughter while grinding organic coffee beans. “And it’s my birthday,” she adds, saving the most important detail to last.

This one-woman coffee shop – if Eva’s off cycling across a country as she often is, Coffee Ride remains closed – has only been in operation for a year. Yet it quickly made an impression, especially in Graz’s cycling community. But even though Coffee Ride is young, the dream behind it isn’t. Eva first wrote a business plan for a lounge-style coffee shop 25 years before as part of her university course.

Following a fascinating life – notable highlights include being the first woman to work in the local brewery since 1495, then going tee-total and cycling across Vietnam – Eva eventually returned to her dream. Though this time, community and cycling defined the business plan rather than an American sitcom.

“There was no water, no real electricity. The first metre and pump were just mud. So there was nothing in here. But I fell in love with the window, and then I said, yeah, for me, it’s big enough.”

In Eva’s own words, she didn’t open Coffee Ride to get rich; she simply didn’t want to skip over this long-awaited moment on her bucket list. Central to the business’ ethos is bringing people together, and like the name suggests – a Coffee Ride is about cycling and socialising together rather than racing or training – it’s usually done on two wheels.

“I organise a coffee ride every Sunday [at 5:30] with two different groups, one 50k and one 100k. The 50k is an easy beginner-friendly ride, and the 100k is a motivated coffee ride.”

Is it only locals, I ask? “No, many tourists come as well. I’m glad that I have very good Google recommendations, and there is like a Facebook for everybody cycling, it’s [called] Strava.” Not content with just getting new friends together, she recently also launched speed dating by bike events – although it’s too early to say if true love has blossomed yet.

With an infectious and generous personality – how many people share their own slice of home baked cake with you? – and plenty of time to chat to everyone that passes through, you soon realise why Eva’s business has been such a success.

“Just come here, and you will never sit alone for the whole day,” she tells me cheerily while spinning her “prediction” wheel. “It says you’ll fall in love.”

The following day, I did return for conversations with fellow caffeine-seekers on the terrace. And I did fall in love. Though it was with Thursday’s newest batch of decadent cakes, baked and delivered herself by Eva on her cargo bike, rather than a cycling soul.

Sip Wine Amongst Urban Vines: Meet Hannes Sabathi at Falter Ego

Austria might not be the first European destination that springs to mind for wine production, but South Styria, the region surrounding Graz, has some excellent varieties. And now, thanks to a long-standing local winemaker – and by long, I mean since 16 years old – Hannes Sabathi, the city even has its own wines and production once more at Falter Ego.

Not that Hannes is reinventing the wheel. Rather he is giving it a second spin.

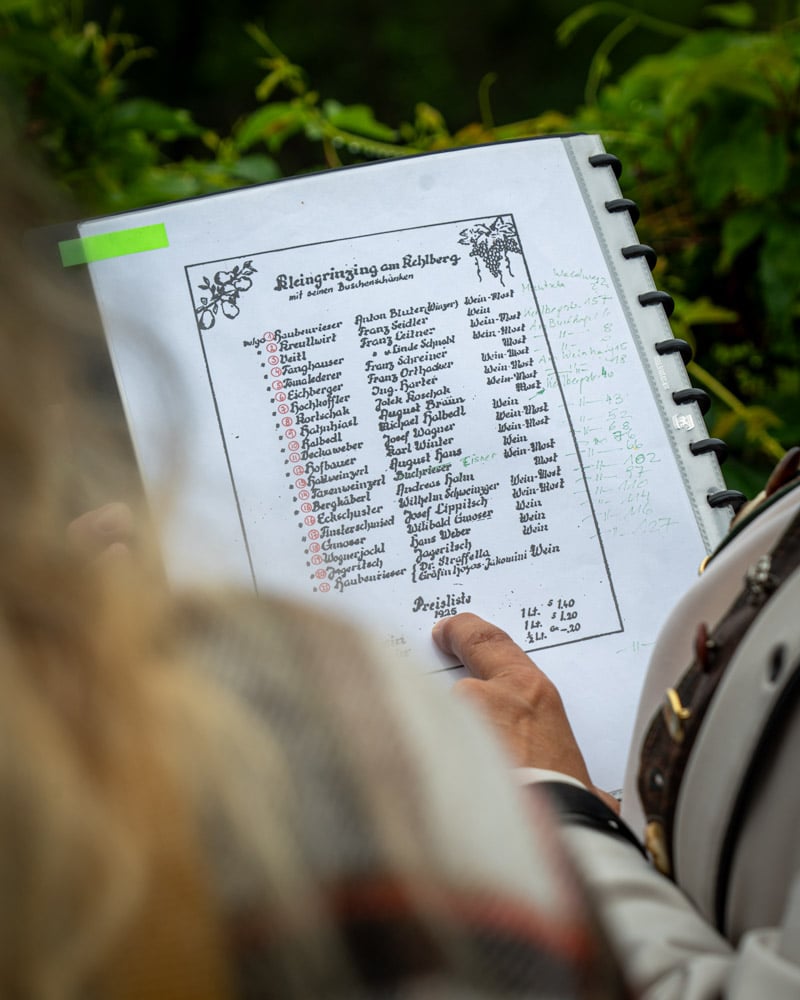

“History shows us that they produced wine here a really long time ago. And that was also a sign for me, of course,” he tells me as we admire the vines sloping down the Kehlberg – the sloping nature of wine growing being a federal requirement.

Stepping inside the half-timbered old treading room, I see what he means. The year 1665 is engraved on a stone inside, reinforcing the belief that it was likely the church who once owned this wine making land.

Tracing the public walking trail flanked by vines and visited by the occasional deer, we reach a flat clearing with dancing butterflies and a sign explaining the winery’s play-on-words name. Falter translates to butterfly in German, and the winery is a favourite spot for the endangered Easterluzei species.

Returning to the modern glass-fronted tasting room – where pre-booked, private tastings occur – we commence the most important task: tasting the wines.

“When our generation stepped in, winemaking really got a boost because you had highly educated young people, and sometimes they were able to travel the world to see how other regions are doing it,” he explains while pouring me a glass of Grauburgunder (Pinot Gris).

“They brought back a lot of knowledge, and it was more than just winemaking. It was sort of a passion, and then they also did a lot of renovation in the cellars.”

Soon after, we work our way through a handful of glasses of crisp Sauvignon Blanc and the dandelion-hued Gelber Muskateller (Muscat), the dolomite terroir apparent in each.

I ask Hannes, a self-proclaimed ‘terrain connoisseur’, if it was more challenging bringing an old set of vines back to life than starting fresh, to which he quickly shakes his head.

“Maybe they didn’t know so much about the soil [then] than what we do now, but they tasted the wines, and they saw the quality. That’s important.”

As Hannes discusses production with another guest, I strike up a conversation with Gabriele Blaschitz, owner of the estate.

“You have an intact nature. You have lakes. You have all the advantages and none of the disadvantages of big cities,” she replies to my question about what makes her home city so special”.

After listing how all her favourite things to do in Austria – “We have an opera house, we have theatre, we are a city of design and we are the Genusshauptstadt [Capital of Culinary Delights] of Austria” – are all available right here, she ends with a familiar comment I’ve heard from everyone I met.

“For me, it [Graz] is just the right size.”

See Classical Concerts with a Contemporary Twist: Meet Mathis Huber at Styriarte

Design, cuisine and culture are Graz’s trademarks – all unsurprising in a country where classical concerts and composers are a common thread. However, Graz’s largest event – Styriarte, founded in 1985 – has been introducing contemporary twists.

On a quest to meet Mathis Huber, Styriarte’s intendant since he turned 25 years old (“a while back now”), I find myself stepping through the doors of their head office, the gorgeous Palais Attems. A splendid building of frescoed ceilings and 17th-century Flemish tapestry-hung walls, it’s within these easily overlooked walls that many performances have historically taken place. But for Huber, it was time for something new.

“Every time we play in musical formats, they [the composition and style] are 100 years old or 200 years old,” he tells me in a particularly stately hall.

“Something is good for 100 years, maybe it’s good for all time. But now we see that the audience has changed his interests so now we watch our concerts two times a day, two times in one evening. We’ve had to make it shorter”.

I soon learned that making Graz’s main cultural celebration more accessible has been one of Huber’s drivers for years. “Our ticket price policy, for example, is we have very high and very low prices,” he explains, highlighting that the two prices subside each other so as not to exclude parts of society. Though by his admission, there’s more to do – “€24 is not nothing”.

Perhaps more fascinating was how COVID and Graz’s aim to become Austria’s cycling capital had played a role in changing the festival’s structure.

“We also have concerts in the mountains”, he explains of the new venues chosen. “We had a project last year near the lake [Thalersee] northwest of Graz where Arnold Schwarzenegger was born.”

For me, the most fascinating initiative was the launch of Fahrradkonzerts, literally Bicycle Concerts.

“With the cycle concerts, we can show a big part of the city in one concert. We have five positions, and we go by bicycle from position to position together with 80 bicycles through the streets and become the king of the traffic”.

But why should travellers make the extra effort to come to Graz when concerts are commonplace across Austria, I ask?

“We play, first of all, for our local audience,” came the wholesome and non-tourism-focused response. “We like guests from everywhere, but Graz is not such a tourist [destination] like Salzburg or Carinthia”, he continues, making it clear that for a more local experience, Graz wins – going as far to say it’s incomparable to almost overrun Vienna.

Community and Creativity: Meet Alois Kölbl at St. Andrä Church

Across the river, Gries is the kind of district where murals of Cicero quotes sit alongside a striptease joint. It’s also a district where gentrification is being fought by community initiatives.

A different world from the grand walls of Palais Attems, street art is abundant here. The work of Yugoslavia-born Mario Paukovic, one of Graz’s mural makers, is particularly prolific. But while it might be typical in any non-Old-Town European district, seeing it inside a church is arguably less common and far more controversial.

Shaking hands with sprightly Alois Kölbl, counsellor of St. Andrä Church, I soon realised that this sacred space operated differently from those that I was used to. It’s not often you see the words “science” and “fiction” painted in lime green above the crucifix on a church’s exterior.

At first glance, you might assume it was a decommissioned church turned into an art gallery. But it’s still very much in service – both to God and the community.

Stepping inside, there’s a lot to process. A mirror-ball-like altar, side chapels with red graffiti, contemporary stained glass windows and a plush, jumpsuit-orange chair where a lectern should be.

“It’s not necessary to be a religious artist to decorate here, but to be a good [Austrian] artist,” Alois chuckles as we stroll the space, a choir practising hymns on stage.

It quickly became clear to me that Alois, perhaps, hadn’t initially been keen on the transformation when he arrived at the church in 2017. Though now, he has more than warmed to it.

“Every Sunday, we host a mass in both Pidgeon and Spanish due to the Latin and Nigerian communities in the neighbourhood,” he continues while pointing out more art pieces. “And once a month, we all celebrate together with an international mass.”

His youthful disposition clearly plays a part in supporting the community, and by visiting one of Europe’s more unique houses of worship, you can contribute to the community projects, including helping with rough sleeping in this less-wealthy quarter of the city.

Shop and Dine: Meet More Artists, Designers and Farmers Across Graz

As you explore Graz and beyond, it’s hard not to strike up conversations with crafters and tastemakers, multi-generation farmers and artists. This former European Capital of Culture and current UNESCO City of Design delivers plenty, though seemingly always with sustainability and consideration for the future in mind.

Meeting Susanne Huber, the sustainable fashion designed at Peaces.bio she tells me how sourcing is her key concern – “I have to know who made these clothes, so I couldn’t expand the business if it means moving the production out of the country” – while the teams at social-project shops such as tag.werk tell me just how important their circular, and community-focused, economy is.

On the outskirts of Graz, at Fattingerhof – one of Styria’s signature rustic Buschenschank dining spots – I met young farmer Helena Fattingergr. “‘I want to keep the family business running, but it’s quite a challenge,” she admits to me. “I need to look at what I can do differently to keep living from it’”

And that, for me, is exactly what tourism, or travelling, or whatever you want to call it should be. Not just meeting the locals but supporting them and ensuring these destinations stay true to themselves and don’t become theme parks, as Philip Florian and I had discussed over that first coffee.

Settling in for my final delicious dinner in the dimly-lit, snug dining room of Mohrenwirt, I open the menu to be greeted by the names of all suppliers. I can even see who – and where to meet – those who weaved the baskets that the backhendl, a typical fried chicken dish, is served in.

“This is made by chef Romana Pieper,” my server says, settling down a tall, thin glass of post-dessert schnapps. ”It’s made with pines from south Styria that she collects in the forest and stores for at least six weeks before distilling”.

Knocking back the fiery liquid, I was reminded once again that Graz has so many makers you barely need to look for them. It can be as simple as sitting down and waiting for them to come to you.

This article was produced in partnership with Graz Tourism. All editorial content is, as always, my own.