On the surface, that sounds reasonable, who doesn’t like more direct democratic processes? But local zoning has failed to address the problems the bill targets, and it is predictable that it will continue to fail, so long as political engagement maintains its current form. In many places, city-by-city control could work, but California is such a jigsaw of localities that each city has incentives to keep following business as usual, which means, zoning restrictions to prop up property values, which inevitably lead to housing shortages and unsustainable costs for anyone who isn’t getting the land value windfall.

Even those getting the windfall are trapped into non-optimal decisions by housing immobility. That immobility has been exacerbated property tax freezes and rent control, more popular, but misguided, attempts to fix housing affordability. Those policies are short term fixes that only benefit those currently in place, while creating long term problems and extra burdens for any new residents or anyone who makes a small move.

Fixing zoning at a state level, in order to open up more infill development with good access to jobs and transit had some promise. The hope was that while individuals might vote against this when it’s in their backyard, they’d accept it as an overall social program. But as the bill’s history shows, political support here is hard to come by too. The ethos of localism is too deeply ingrained to admit to it’s own harms.

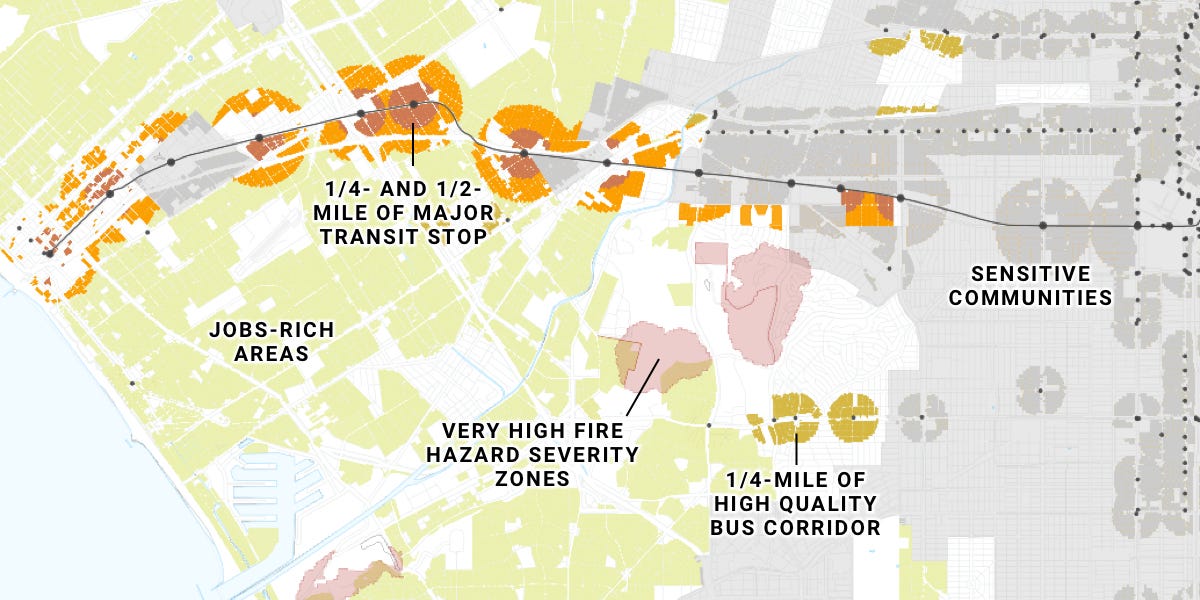

Even before the shelving, the bill was forced to create many exemptions. A study by Urban Footprot helps to get a grasp of how these alter the potential areas of impact. It’s still a bit hard to understand, but what I see is that the “sensitive areas” exception has a huge impact on the transit oriented part of the bill. That is especially worrisome. Why? Because the groups most impacted by the housing shortage and those represented by the sensitive areas are generally similar. If these communities start out as conceiving of denser development as a problem, rather than as a part of the solution it’s hard to imagine political support emerging overall.

There’s a lot of “great” talk about aspirations and commitment to the problem, but when it comes to laying out a plan, everyone wants an exception. I’m a bit skeptical that the local customization is all that useful or necessary. I’m even more skeptical that it wouldn’t be abused. But politics being what it is, perhaps the best way out would be the suggestion of Redwood City Councilwoman Shelly Masur, to give communities a chance to create their own plan, but have policies that take effect if they haven’t achieved goals.

To bring this back to my home turf, Chicago doesn’t have the statewide problem California does. For the most part housing in downstate Illinois doesn’t affect Chicago. Even suburbs are somewhat isolated in effect to Chicago itself. But what Chicago does have is an extreme Aldermanic preference where city council generally won’t do much city wide. The exception to this has generally been Chicago’s mayors who often overrule the city council.

There’s a lot of problems to that system, but it’s worth noting it as the reality when pursuing any change in Chicago.